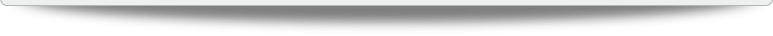

追忆费城交响乐团1973年访华演出描述:奥曼迪指挥中央乐团

两个乐团成员互赠乐器

虽然,费城交响乐团的乐手考试不需要特别考察乐手的外交技巧,但是,正是外交让费城交响乐团作出了20世纪文化历史上最伟大的贡献。35年前的9月,费城交响乐团作为中国大陆向西方开放的一个有利的筹码进入国际舞台。

这是一个重大的筹码,它是一架满载着希望开启在二战前就曾非常热闹的演出舞台的音乐家的航班。这是自从毛泽东领导中国之后,第一支在中国演奏的美国乐团(伦敦和维也纳爱乐乐团早来了几个月)。访问演出是源于尤金·奥曼迪于1971年尼克松和基辛格秘密访问中国后,写给总统的信。奥曼迪提出派遣乐团访华的建议是深思熟虑的。而费城交响乐团则是尼克松的不二之选。一年前,尼克松曾在乐团的周年纪念音乐会上被授予荣誉称号。奥曼迪也是访华的合适人选。因为30年前,他曾经在澳大利亚指挥过一个中国救济音乐会。乐队访华演出前,双方经过严谨而平静的谈判。谈判过程非常复杂。不像是人们想象中,费城交响乐团的经理索克罗夫(Boris Sokoloff)与一名中国的经理坐在一起,给出日程和一个乐手、曲目以及住宿和旅行所需物品的单子那样简单。双方的交涉都是通过隐蔽的外交途径进行的。

如何在一个以自行车和马车作为主要交通工具的国度,运送104名乐手、乐器、舞台设备,还有行李箱呢?那里有没有降落波音707的地方?哪里可以让中国人为需要窗垫、早上吃奇怪得像鸡蛋和土司还有咖啡一类食品的西方人安排住宿?

在尼克松总统积极的推动下,乐团访华一事基本准备就绪。然而,毛泽东的夫人,喜欢发号施令的曾当过演员的江青却在北京拖延乐团访华的进度。当然,江青必须审核乐团的演出曲目,不是所有的作曲家都适合革命时代中国的模式。奥曼迪推荐了很多作品,最终被允许演奏德彪西、贝多芬、舒伯特、勃拉姆斯的作品及罗伊·哈里斯的第3交响曲,还有《黄河钢琴协奏曲》,一部用出色的共产主义方式谱写的作品——由匿名的创作小组写成。

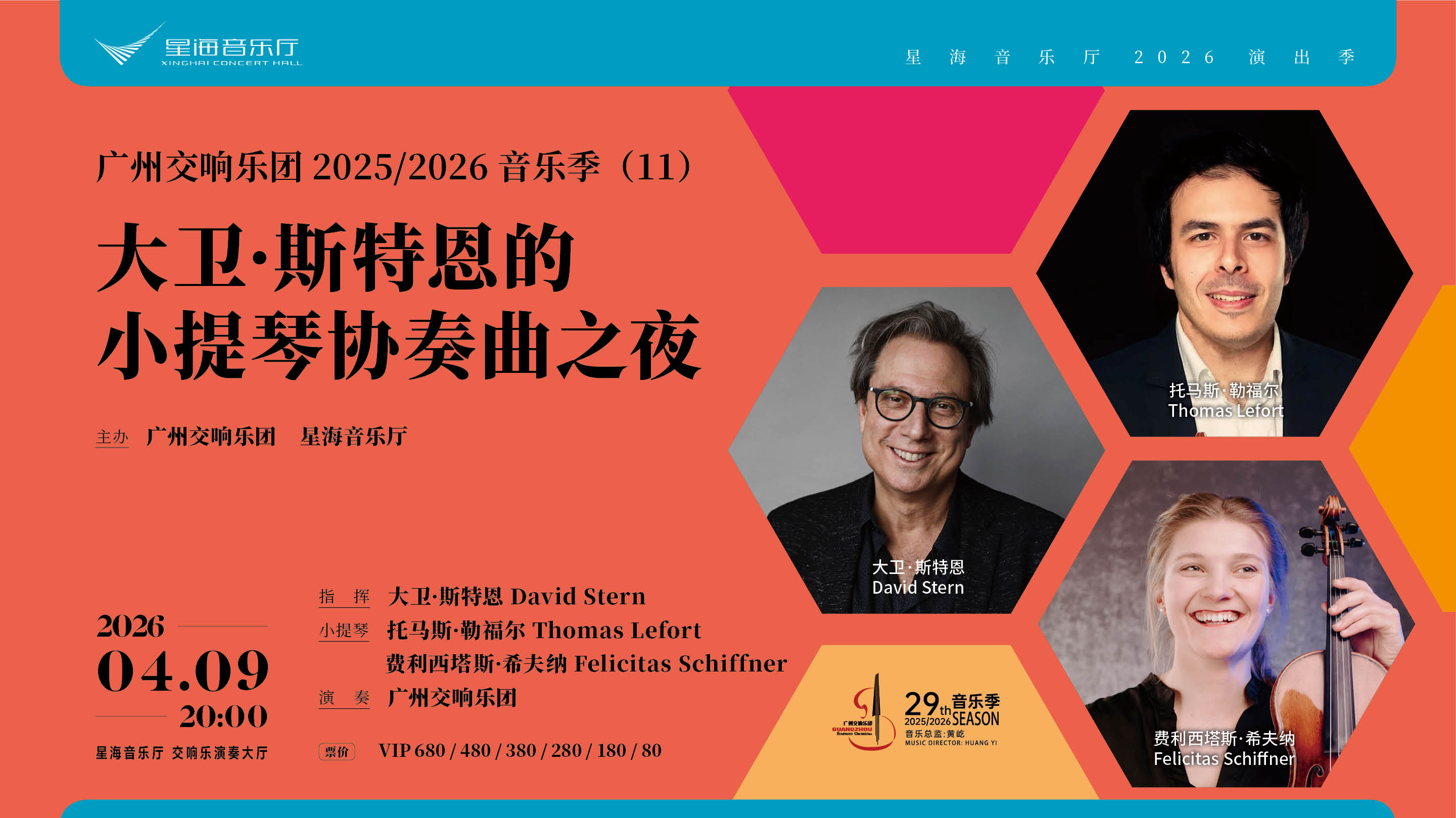

1973年9月18日费城交响乐团音乐总监奥曼迪与乐团其他成员参观长城

尽管乐手们不能带上他们的配偶访问中国,还必须面对霍乱的侵袭,但全体乐手依然憧憬着这次不平常的中国之行。中国限制随行人员和舞台人员的数量,最后精简到只有乐团总经理索克罗夫先生,后勤主管约瑟夫·圣塔拉斯迪(Joseph Santarlasci),奥曼迪夫妇,乐队主席华顿·巴厘(Wanton Balis)夫妇,评论员路易斯·胡德(Louis Hood)和5名新闻记者——《纽约时报》的乐评人舒恩堡、费城公告专栏作家Sandy Grady、Kati Marton和第10频道的摄影师以及本人。这些成员加上乐队正好装满了这次旅行专用的波音707飞机。

访华演出的重要性使得乐手的旅途显得非常漫长。在费城老国际机场出发后,乐队在檀香山逗留了一个晚上。在那里小号手吉尔·约翰逊(Gil Johnson)丢失了他的护照,需要发出请求电报才能让他继续留在飞机上。然后,他们从檀香山到东京,短暂停留之后,他们辗转到达了上海。这次旅行十分富有戏剧性。因为在东京和中国之间没有任何航线。没有人知道在中国什么在等待着他们。“费城”要来临中国了!飞机在旷地上低空飞行,摇晃着在一个小型机场降落了。中国为奥曼迪一行精心准备了一个欢迎仪式:鲜花、加厚的沙发椅子、茶,让乐手们在北京着陆之前有机会舒活一下身体。

巴士鸣着喇叭,与全天占据北京马路的自行车流分开行走。巴士途经人民大会堂,据闻中国共产党刚刚在那里举行了第十次代表大会。随后,乐手被周到地安排入住到房间,房间外的门上都写着乐手的中英文名字,走廊里站着紧张等候客人的侍者,他们的任务之一就是随时补充房间热水瓶中的开水。白天,乐手们参观了长城、明代陵墓、颐和园和紫禁城。乐手们还经常可以听到当地的音乐家演奏二胡、琵琶、笙,还有其他的民族乐器。

早起床的人观察到严肃的中国人穿着毛泽东式的长衫在街道上练太极拳。一两天之后,小号手迈克玛斯(Don McComas)、长号手多森(Glenn Dodson)等几个人拿出了他们的秘密武器——飞盘。他们玩起飞盘,街上好奇的人们立即围观,更有中国人加入了他们的游戏。小小的飞盘穿越了语言和文化的屏障。

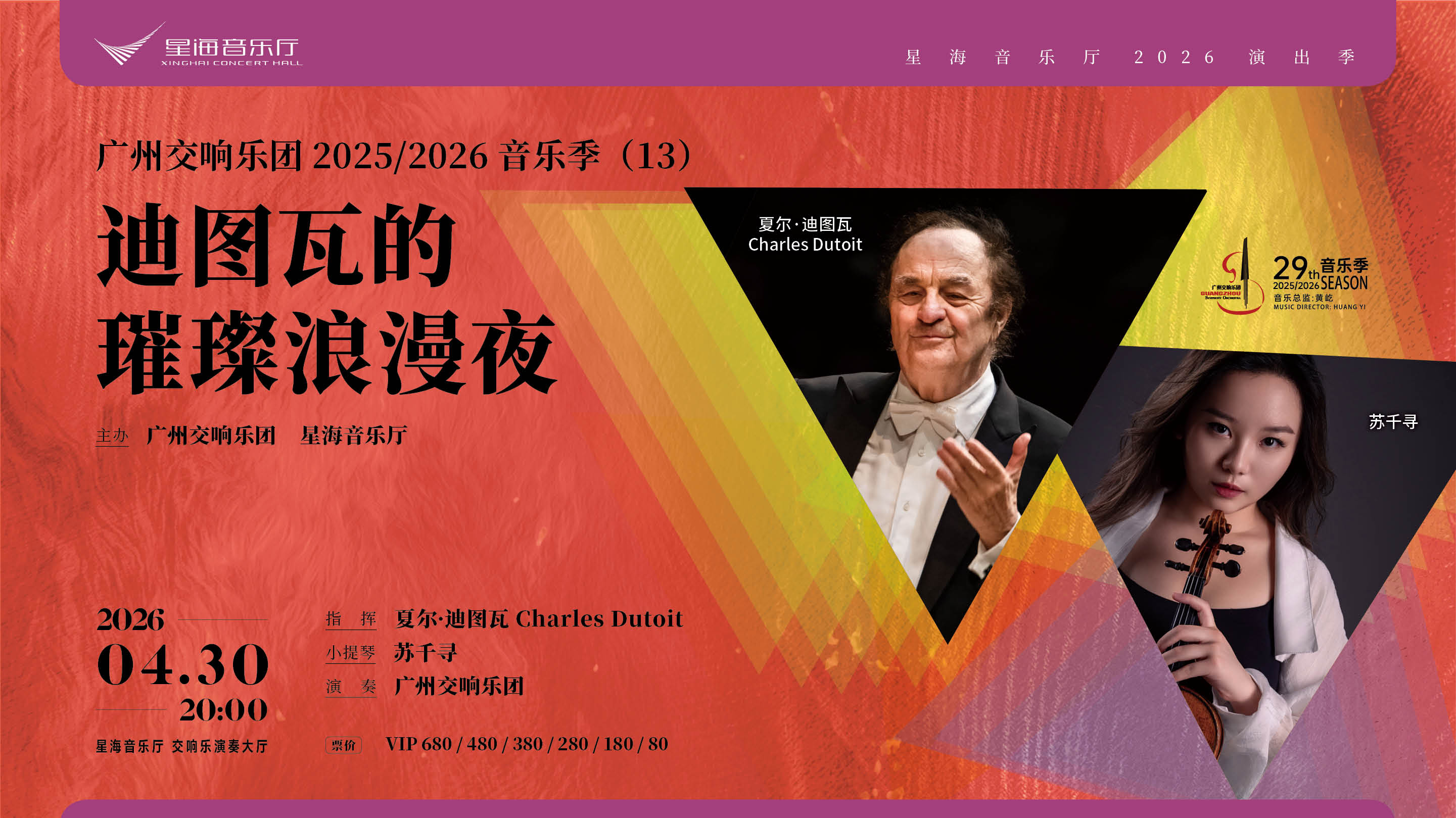

1973年9月费城交响乐团音乐总监奥曼迪排练指挥中央乐团

当音乐家在大街上行走时,人们纷纷投以好奇和惊讶的目光。毕竟,西方人25年没有在这些街道上散步了。骑车的人停了下来了,街上的群众看到这么多的外国人,也愣在那里。第二天早上,乐队首席诺曼·卡罗(Norman Carol)和一些其他的小提琴手加入了街道上中国人购买油煎饼的“长蛇”般的队伍。中国人感到十分震惊。他们疑惑着,是否需要给队伍中给这些外国人让位呢?他们该不该放弃早餐,只是呆看呢?两个都是非常可能的选择。最终,长蛇队伍被打乱,小提琴家们被推到了前面。早餐成了一个观众的游戏。

哦,音乐呢?是有一些的。奥曼迪举行了一次排练并会见了当地的指挥家李德伦及演奏《黄河》的钢琴家殷承忠。然后,乐队被邀请到北京老城墙边一座破旧混凝土建筑里,聆听中央乐团的演出。中央乐团的条件很差。乐手拿着有缺口的和用胶粘过的乐器,他们使用的是手写的、粘贴在一起旧乐谱演奏。李德伦作出了最大努力,但是他排练的贝多芬简直不像样子。这些乐手从1966年开始从事采煤和田间劳动,几个月前,他们突然被招回,重拾西洋音乐。

李德伦很有礼貌地邀请奥曼迪指挥。奥曼迪微笑着面对紧张的乐手,举起指挥棒——重新塑造交响乐团。这群沮丧的人们记起了他们的职业,他们把弓子放在弦上,巴松也找到了调,这群“文艺工人”又成了音乐家。费城人向乐团赠送了一些专程带来的乐器,大家一起握手,交换关于乐器的看法,拥抱,费城人甚至可以看到中国人眼睛里的眼泪。这次短暂的会面带来了长期的交流和合作。小提琴手莫吉尔(Leonard Mogill)访华后,长年给他的中国同行赠送乐谱。打击乐手阿贝尔(Alan Abel)尝试了中国民族乐器,也给中国的研究机构提供美国人演奏什么乐器的信息。

乐团在北京演出了几场音乐会。对哈里斯和德彪西,观众似乎难以理解;而贝多芬和黄河协奏曲则受到鼓掌喝彩。听众是什么人?江青那些年已经关闭了大学和音乐学院。这些观众难道都是官员吗?身着过时的西服,江青无处不在,微笑着站在乐手的中间被美国艺术家拍照。音乐家们参加了盛大的宴会,品尝了海参,梅子酒和其他珍馐百味.厨师们还当众表演了出神入化的厨艺。

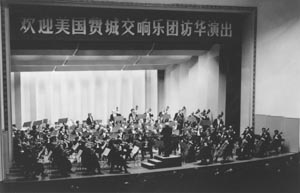

1973年9月费城交响乐团在音乐总监尤金·奥曼迪的带领下首次在北京演出

行程继续。到上海的航程是乘坐一架俄国造的旧式飞机,座位很狭小,飞行中只有泡泡糖供应。(30年后美国航空公司也照搬了这种模式。)乐手在上海看到了欧洲殖民者遗留在那里的痕迹。从最高12层的建筑上,他们可以看到高粱地伸展到黄浦江的南面,绚丽的航船,和中国的油轮。乐队被邀请坐游船在江上游览,在船上他们听到了一个6人乐队用传统乐器即兴演奏古老的曲子。

主人极力让乐队参观工业展览和党的纪念碑,但是费城人选择了购物——这让当地人很惊讶。这些展览中的金属粉末技术彰显着中国潜在的实力,我们则匆匆略过。在一家“第10号”商店乐手们买到了有鱼皮隔膜的竹笛,还有一些装饰品。在被特殊许可接待我们的友谊商店,有卷轴和属于古老中国的物品出售。公共汽车在看到费城人经过的时候就停下来。小提琴手帕斯奎勒(Robert De Pasquale)在街上散步,听到楼上传来了小提琴声。他冲进建筑物,跑上楼找到了正在练琴的学生。他给了这个惶恐的孩子上了一个小时的课。

当时的中国是禁欲的和清教徒式的。男孩子和女孩子不能走在一起,没有外表上的情侣。每个人都在为党工作。这次旅行结束,在费尔班克斯(美国阿拉斯加州城市),圆号手琼斯(Mason Jones)和我在雪中散步,听到学校里的四重奏在演奏用普塞尔的作品改编的曲子。琼斯说:“这是我在中国所没有听到的。”我笑着问他:“是什么呢?”琼斯回答:“是对位。”

这究竟意味着什么?新中国已经曙光初现,随着毛泽东的逝世,江青等人明白旧中国即将消亡。中国需要非政治的目击者来见证它的新生和重新开放,交响乐团是最合适的角色。

对于美国人来说,交响乐团代表其最优秀的文化。音乐增进了两国的友谊,中国已经做出了对于西方人最隆重的欢迎礼仪。我们在中国看到了最后的伟大的文明,并在回国之后还为之惊叹。但是,费城交响乐团打开一扇关闭了25年的大门。乐手们发送邮件、乐谱和杂志给北京的同行们。贝司手托里罗(Carl Torello)回到家里就成了针灸疗法的拥趸。大提琴手格罗德泽(Harry Gorodetzer)兴奋地到处交朋友,把很多通信地址带回了美国。中国人给乐队送来了铜锣和打击乐器。我们留下了唱片、乐谱,甚至一些乐器。这些东西开启了艺术家和学者、商务领导和学生之间的广泛交流。

琼斯的回答耐人寻味。中国的民族音乐中没有对位;在中国的生活中也没有对位,但是交响乐团,它的音乐和它的表演已经提供了一个危险的价值取向空间。在乐团离开后,江青立即禁止了在中国的音乐厅表演舒伯特。

The Philadelphia Orchestra: Learning Chinese

By Daniel Webster

01 Feb 2008

Revisiting The Philadelphia Orchestra’s historic 1973 tour to China.

Philadelphia Orchestra auditions don't include discussions of diplomatic initiatives, yet it was in diplomacy that the Orchestra may have made its greatest single 20th-century contribution to cultural history. Just 35 years ago this September, the Orchestra entered the world scene as a bargaining chip in the opening of mainland China to the West.

It was a large chip, but disguised as a planeload of musicians hoping to restart what had been a busy musical scene before World War II. This was the first American orchestra to play in China since the Maoist revolution and bloodbaths (the London and Vienna philharmonics had preceded it by a few months). The tour had its roots in Eugene Ormandy's 1971 letter to President Nixon followed by the secret visit to China by Nixon and Henry Kissinger.

Ormandy's proposal to send the Orchestra seemed a cautious next step. Philadelphia was the natural choice for Nixon, who had been honored at the Orchestra's Anniversary Concert a year before. Ormandy was acceptable, too, because 30 years before he had conducted a China Relief concert in Australia. The quiet negotiations that preceded the tour must have been extraordinary. Talks were intricate. There was no such thing as having Orchestra Manager Boris Sokoloff sit down with a Chinese impresario, give him dates and a list of players, repertoire, and housing and travel needs. Communication was through shadowy diplomatic ties.

How do you move 104 musicians, instruments, stage equipment, and trunks in a nation that moved on bicycles and horse carts? Was there a place to land a 707 jet? Where could the Chinese house Westerners who wanted beds and who ate queer things like eggs and toast--and coffee--in the morning?

It all happened because Nixon was pushing here, and Mao's wife, the commanding former actress Jiang Qing, was pulling from Beijing. Of course, Jiang Qing had to approve the repertoire and not all composers fit the revolutionary Chinese template. Ormandy proposed many programs, and was finally allowed to play Debussy, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Roy Harris's Symphony No. 3, and the Yellow River Concerto, a work composed in the best Communist way--by an anonymous committee.

Good will was everywhere, even after the musicians found that they had to have cholera shots and could not take spouses with them. The Chinese limited the tour party to players and stage crew, Mr. Sokoloff, logistical magician Joseph Santarlasci, Mr. and Mrs. Ormandy, Orchestra Chairman C. Wanton Balis and his wife, publicist Louis Hood, and five members of the press: New York Times critic Harold Schonberg, Philadelphia Bulletin columnist Sandy Grady, Kati Marton and her cameraman for Channel 10, and myself. That number comfortably filled the PanAm 707 examined and approved for the trip.

The gravity of the tour was slow to gather for the players. After a sendoff from the old international hangar in Philadelphia, the Orchestra spent a night in Honolulu. There trumpeter Gil Johnson lost his passport and required desperate cables to allow him to continue on the plane. The next flight was from Honolulu to Tokyo, then, after a pause, to Shanghai. The tour was suddenly magnified. No travel existed between Tokyo and China--or between much of anywhere and China as far as that went. No one had a hint of what awaited them in China. Fay Chen (Chinese for Philadelphia) was coming. The plane came in low over tilled fields and rolled to a small terminal. An elaborate ceremony for the Ormandys with flowers, overstuffed chairs, and tea gave players a chance to stretch before heading to a night landing in Beijing.

Buses, horns blaring, parted the waves of bicyclists that day and night owned the road into Beijing. The buses passed the Great Hall where, it had been rumored, the Communist Party had just held its 10th Congress. The players were carefully placed in rooms, their names in English and Chinese by the doors, in a hotel with hallways full of nervous waiting staff whose duties consisted of refilling thermoses of tea in the rooms--day and night. The Orchestra was seeing the dawn of a new age in China, but it was seeing the sunset of a great tradition, too. The players' days were filled with visits to the Great Wall, the Ming Tombs, the Summer Palace, and the Forbidden City, in which Mao lay dying. Virtuoso musicians playing erhu, pipa, sheng, and other folk instruments performed at every turn.

Paradoxically, the Communists were showing treasures from civilizations they despised. But only so much forced feeding, even of epochal treasures, can be maintained. Early risers watched the streets where solemn Chinese in Maoist pajamas practiced Tai-chi. After a day or so, trumpeter Don McComas, trombonist Glenn Dodson, and others showed off their secret weapon--frisbees. They began tossing them and crowds gathered. The Chinese joined and frisbees flew across language and cultural barriers.

For the musicians to be on the streets challenged Chinese credulity: Westerners had not walked the streets for 25 years. Riders stopped their bikes and walkers froze at the sight of such exotic beings. On the second morning, Concertmaster Norman Carol and some other violinists joined the snaking line of Chinese buying flat pancakes fried on charcoal grills in the streets. The Chinese were shaken. Should they give their place in line to these foreigners? Should they abandon breakfast and just gawk? Both seemed practical choices. The violinists were pushed forward as the line broke apart. Breakfast was a spectator sport.

Oh, and the music? There was some. Ormandy held a rehearsal and met the local conductor Li Teh-lun and Yin Cheng-Chung, the pianist for Yellow River. Then, the Orchestra was invited to hear the Central Philharmonic in its cracked concrete building with rattley windows that stood north of the scar marking the dismantled medieval wall that once surrounded Beijing. The orchestra was pitiful. Members held chipped and glued instruments and they played music that was hand copied and pasted together from decades before. Li did his best, but the Beethoven they rehearsed was scarcely recognizable. These musicians had been mining coal and doing field work since 1966, and a few months prior they were suddenly brought back to reintroduce Western music. Li bowed and asked Ormandy to conduct. Ormandy took the baton, smiled at the nervous players, raised the baton--and made an orchestra. The tattered group remembered who they were: They dug their bows into the strings, the bassoons found intonation, and these "cultural workers" were musicians again. The Philadelphians presented some instruments brought for the occasion and everybody shook hands, traded ideas about instruments, even hugged and saw tears in Chinese eyes. From that meeting came about long-lasting exchanges. Violist Leonard Mogill sent scores to colleagues for years after the tour. Percussionist Alan Abel tried the folk instruments and gave the Chinese seminars in what the Americans played.

The Orchestra played concerts in Beijing. Harris and Debussy were mysteries; Beethoven and the Yellow River Concerto were applauded. Who were the listeners? Chiang Ching, as Mao's voice, had closed the universities and conservatories that year. Were these all party functionaries?

In outdated Western clothes, Jiang Qing was everywhere, smiling, mingling with players, being photographed in the midst of American artists. The banquets that filled the evenings introduced musicians to sea cucumbers, high-octane plum liqueur, and the most brilliant cooking and presentation anyone could recall.

So the tour spun on. The flight to Shanghai in a worn Russian Ilyushin showed China a generation ahead of its time. The seats were cramped and only chewing gum was served on the flight. (American airlines were to copy that format 30 years later.)

The players saw in Shanghai the remnants of a city once divvied up among European governments. From the highest building in the Bund--12 stories--players could see sorghum fields stretching to the south of the Whangpo River, ornate sailing ships, and Communist bloc tankers. Glass towers fill that panorama now. The Orchestra was treated to a cruise on the river where they heard a shipboard band of six playing traditional instruments in an ancient tune with improvised variations that grew to span almost the entire trip. Here was Old China at its fading best.

The hosts tried to force visits to industrial displays and Party monuments, but the Philadelphians went shopping--to the astonishment of the natives. Yet in those displays of powdered metal technology lay the first signs of the new China's potential might. We skipped it. In Department Store No. 10 players bought bamboo flutes fitted with fish-skin membranes, and some trinkets. There were supervised visits to the approved Friendship Stores where scrolls and other reminders of old China were on sale. Local buses stopped at the sight of the Philadelphians. Violinist Robert De Pasquale, walking the streets, heard a violin. He dashed into the building, up the stairs and found a student practicing. He gave the astonished boy an hour's lesson.

Maoist China was celibate and puritanical. No boys and girls walked together, no couples were apparent. Everybody was at work for the Party. When the tour halted abruptly in Fairbanks (no new crew was available to fly), hornist Mason Jones and I walked through snow to see the First Dance Quartet at the high school. They opened with José Limon's super-sensuous Moor's Pavanne, set to a Purcell score, a retelling of Othello in passionate intertwining intensity. At the end, Jones said "That's what I missed in China." "What was that, Mason," I teased him. "Counterpoint," said Mason.

What did it all mean? A new China was scarcely visible over the horizon, but with Mao dying, Jiang Qing and others knew the Old China was moribund. China needed non-political witnesses to see a ceremonial rebirth and reopening. The Orchestra fit that requirement.

For the Americans, the Orchestra represented our culture at its best. We could report that our two musics spoke of friendship, and that China had done its utmost to welcome Westerners. We saw the last of a great civilization, and came home to marvel at it. But the Orchestra had pried open a door shut for 25 years. Players sent mail, scores, and magazines to their colleagues in Beijing. Bassist Carl Torello, his body abbraided by decades at the bass, came home a paraclete for acupuncture. Cellist Harry Gorodetzer had easily made friends everywhere and came home with lots of addresses for letters. The Chinese had sent with them elaborate gongs and percussion instruments. We had left recordings, scores, even some instruments. These were increments in what has become a vast exchange of artists and scholars, business leaders, and students.

Mason Jones's Delphic answer was apt. There was no counterpoint in Chinese music; there was no counterpoint in Chinese life, but the Orchestra, through its music and its presence, had proposed a dangerous alternative. After the Orchestra left, Jiang Qing acted quickly to protect her billion or so non-voting constituents. She banned Schubert from Chinese concert halls.

Daniel Webster is a former music critic of the Philadelphia Inquirer.

|